This article is written by Dr. Dean Chavers and was published in Indian Country Today Media Network on January 18, 2017. It is published here with permission by Indian Country Today Media Network.

One of the first militant actions of Indian protest happened at my home on the night of January 18, 1958. That night the Ku Klux Klan decided to teach the Lumbee Indians a lesson. But the outcome went the other way. We ran the Klan off and they have not been back.

The Klan leader from South Carolina, James William “Catfish” Cole, had announced a few weeks prior that he was going to put the Indian Niggers of Robeson County in their place. The Klan had burned a cross on the front lawn of an Indian woman who was dating a white man. She lived in the little white town of Saint Pauls. Then they burned a cross in the front yard of an Indian woman who had moved her family into an all-white neighborhood in the county seat, Lumberton. Then they announced they were going to hold a rally near Maxton at a place called Hayes Pond.

I say “we” loosely because I was not there. But my classmate Dupree Clark, my cousin Sonny Boy Revels, and his cousin Bruce Jones were all there. I had left the all-Indian school in Pembroke the previous September to live with my grandparents, Purcell and Jessie Godwin, in Dinwiddie County, Virginia. All their kids were gone. They needed help with their 300-acre farm. I lived with them for six years, finishing high school and two years of college before I joined the Air Force.

I was a junior at Dinwiddie High School when the Klan riot happened. The principal, Mr. Ivan Butterworth, called me out of study hall a week after it happened to ask me about the Battle of Hayes Pond, which is what the newspapers called it. He showed me a copy of Life Magazine and asked me if I knew any of the people in the pictures. I had not heard about the riot.

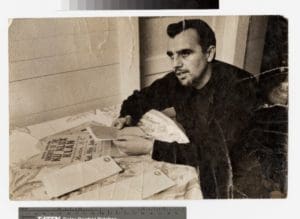

I said, “Yesser, that’s my cousin Sonny Boy in the one picture. And that’s Simeon Oxendine in the other picture.”

He looked at me kind of funny, like he thought I was going to cause him some trouble. “I know Mister Sim,” I told him. “His daddy Sonny Oxendine was the first Indian mayor of our little town of Pembroke. Sim was in World War II, and flew a bunch of missions over Germany. I used to eat at their restaurant next to the garage where Sim worked on cars.”

Sim and Charlie Warriax had taken the Klan flag and draped it around themselves. The picture of the two of them clowning around made the news all over the country. I felt kind of cheated by not being there. Sim wasn’t afraid of much. He had been a waist gunner on a B-17 that flew 25 missions over Germany in 1944 and 1945. You didn’t push him around. He had been on some of the bombing raids over Schweinfurt and seen his share of fighter attacks and flak attacks.

Mr. Butterworth let me go back to study hall in a few minutes. He had been principal when my aunt Claire had gone through Dinwiddie High School 10 years before I did. And he was there when my uncle Foncie finished five years before I did. So he knew us. I learned on the spot that Mr. Butterworth was a control freak who ran a very tight ship. Ivan completely rewrote my valedictorian speech the next year. He certainly did not want any trouble, especially when the country was about to undergo the pain of integrating schools, housing, jobs, and hospitals.

The entire South at that time was still totally segregated. I rode the bus with the white kids right past the black school, Southside High, and the black kids rode the bus past our white school. I was the only minority person at Dinwiddie High at the time. But nobody made a big deal about it. I could have passed for white, but never did. Everybody there knew I was Indian.

Catfish Cole had been trying to intimidate Indians by bringing caravans of cars through the county. There would be seven or eight of them, cruising through Maxton, Saint Pauls, and Red Springs right after dark on a Saturday. Lillie McKoy, who was mayor of Maxton later, said: “They wanted you to see them. They wanted you to be afraid of them.” And most people were.

The Sheriff, Malcolm McLeod, had bothered to go to South Carolina to warn Cole not to come to Robeson County with his rally. McLeod knew from a quarter of a century of experience that it was a big mistake to push an Indian into a corner. Chances are one of you would be hurt or killed, and chances are it would not be the Indian.

Cole was foolish enough to ride around the Indian communities in Maxton, Red Springs, Elrod, and other places announcing the rally over a loudspeaker.

When they got to the pond on Saturday night, there were 50 Klansmen there. But Sim had gotten 500 Indians there. They were armed with rifles, shotguns, axes, pitchforks, and hoes. When Cole got up to start the rally, one of the Indians, Sanford Locklear, shot out the light bulb over the stand. The Klan broke and ran. Sanford had his picture in the paper the next day, holding the rifle he used to shoot out the light.

Cole left his wife sitting there in a ditch in their car. The Indians let out war hoops as they chased the Klan members down the little road. Those boys were scared. One or two of them ran their cars into ditches and had to be pulled out. They went running back to South Carolina and have not been back since.

Cole, who was a radio evangelist on the side, had dared to invade Indian Country despite the warning from the Sheriff. It was ironic that the man who sentenced him to two years in prison was an Indian judge in Maxton, Mr. Lacey Maynor. Mr. Lacey used to cut my hair.

Cole served his time, was shamed in South Carolina, and moved to Virginia, where he stayed for a couple of years. At the end of his life, he moved back to South Carolina and died less than two years later in a car wreck.

Stan Knick, the director of the Native American Resource Center at the local Indian university, said recently, “You wouldn’t hold a Klan rally in Harlem, would you?”

Pembroke was known as the Indian capital. When I was a boy there were maybe 150 white people living in the town, and over 1,500 Indians and a couple of hundred black people. Maxton had lots of black and Indian people, too.

The famous folk singer Malvina Reynolds wrote a song about the Klan roust, called “The Battle of Maxton Field.” Pete Seeger had a modest hit with the song. Malvina came over to Alcatraz Island in 1969 and was a big supporter of the Indian occupation. Her biggest hit was about the little houses that looked like boxes made out of ticky tacky, and they all look just the same.

It was possibly inevitable that I would be involved in the next big Indian protest action—the Indian occupation of Alcatraz Island. That action spurred the takeover of dozens of similar places, including Southern California, the Pomos on Rattlesnake Island, the Pit River occupations that lasted for years, the American Indian Movement occupations at Plymouth Rock and Wounded Knee, and the Indian occupation of Fort Lawton in Seattle.

When I got to UC Berkeley in 1968, I was the oldest Indian undergraduate on campus. Lee Brightman, who had founded United Native Americans (UNA) the year before, was the only graduate student; he was 40 years old. The other two students, LaNada Boyer and Patty Silvas, were both about 20. I was 27, and had spent over five years in the Air Force flying B-52 bombers.

At the end of the year, there were 15 Indian students there, and two of them decided to have a party to celebrate the end of the year. They were sisters, Carmen Christy and Laverne Shepherd. Richard Oakes, Alan Miller, and Gerald Sam were there, trying to talk us into going with them to take over Alcatraz Island. They were all students at San Francisco State.

Being on that prison was the last thing on my mind. All I wanted to do was get through college, get a job, and be normal. It would be 11 years after I finished high school before I got an undergraduate degree. So I didn’t pay much attention to the three from State. I went back to talking to the girl sitting next to me, LaDonna Cottier.

But when the occupation happened on November 19, 1969, someone said we needed to call the press. Richard asked me to go back and do it, and write a press release. He said, “You’re the oldest person here, and you’re the only one who knows how to write.” So I ended up being the Mainland Coordinator for the next two months, talking to Richard several times a day on the phone.

LaNada, one of the originators of the idea, was one of the few who went over the first day and stayed the whole time. I still admire her for that, and the fact that she earned her doctorate degree and worked as the tribal administrator for Fort Hall. LaNada is still our leader, and I am proud to follow her.

Dr. Dean Chavers is director of Catching the Dream, a national scholarship program for Native college students. His next book is “The American Indian Dropout.” Contact him at [email protected] to inquire about scholarships.

This story was originally published January 25, 2015.

I found this article just roaming around on the internet. Having grown up in Lumberton, NC during this time, I vaguely remember the situations of the Klan driving through neigborhoods in their cars. I vividly remember Sheriff Malcolm McLeod. Also, after graduating from Pembroke State University in 1968, I know first-hand how proud the Lumbees are. I couldn’t have grown up in a better place at the time. This article is a fantastic recount of the situation and pride back in those days.