Healthy eating in the modern world is not always easy. Fast food and prepackaged foods offer inexpensive and easy alternatives to healthier foods or cooking from scratch. Even in remote locations, you can find snacks like burgers, chips, candies and sodas. However, these kinds of foods can be harmful to our health in the long run.

Diet and nutrition play a crucial role in our overall health. A poor diet can have an especially dramatic impact on the lives of elders. American Indians and Alaska Natives in particular face a predisposition to obesity and diabetes. Historically, however, Native people did not face these health disparities. History shows how Native communities have come to face these disparities and points to how these trends might be reversed.

Disparities Related to Diet

Research suggests that the “modern” western diet is detrimental to the health of all consumers and especially elders. American Indian and Alaska Native elders face disparate rates of obesity: nearly 40 percent of men and more than 46 percent of women are obese. These rates are highest among elders age 55-64 and are lower among older elders.

The rates of diabetes among Native people are more striking: more than 16 percent have diabetes, a rate more than twice as high as that of the general population in the United States as a whole. Among Native elders, 30 percent — nearly one in three — have diabetes. Some Native communities suffer even higher rates of diabetes. The Pima of Arizona have seen rates of diabetes as high as 60 percent in their community. The consequences of diabetes left untreated include amputations, blindness and death. Native people are twice as likely to die from diabetes.

A variety of factors contribute to the high rates of diabetes and obesity among Native elders. Along with the predisposition for these conditions, diet, exercise and other factors are important contributors. It is important to note that while Native people are predisposed to these conditions, they were very rare just 100 years ago.

History of Native Diets

Four time periods describe the American Indian and Alaska Native diet before and after European colonization.

1. Pre-Contact Foods and Diet

1. Pre-Contact Foods and Diet

Diets have changed dramatically since the introduction of European foods into the diet of American Indians and Alaska Natives. The diets of Native ancestors contained more complex carbohydrates (such as whole grains, peas, beans, potatoes) and fewer fats (such as meats, dairy products, oils). The variety of cultivated and wild foods eaten before contact with Europeans was as vast and variable as the regions where Native people lived.

Foods harvested generally included seeds, nuts, corn, beans, chile, squash, wild fruits and greens, herbs, fish and game, including the animal’s meat, organs and oils. Foods were dried, smoked, stored for later use. While diets vary from nation to nation, traditional foods consisted of those that could be gathered and hunted in the local area, and sometimes included agricultural products like corn, squash and beans, which were introduced before European influence on diets.

Indigenous agricultural practices utilized environmental cooperation as shown by the “three sisters (corn, beans, and squash)”. Corn draws nitrogen from the soil, while beans replenish nitrogen. Corn stalks provide climbing poles for bean tendrils, and broad leaf squash grows low to the ground, thus shading the soil, keeping it moist, and deterring the growth of weeds.

2. First-Contact Foods and Changes

In the 15th century, European settlers brought sheep, goats, cattle, pigs, horses, peaches, apricots, plums, cherries, melons, watermelon, apples, grapes, and wheat. Spanish sheep changed the lifeways of the Navajo (Diné). Europeans adopted foods indigenous to the Americas such as the tomato, potato, and chile.

3. Government-Issued Foods and Forced Relocation

The shift in the way American Indians and Alaska Natives eat came as a result of being removed from their homelands and relocated to reservations. The Federal Indian Removal Act of 1830 forcefully removed more than 100,000 American Indians to Oklahoma Territory. In 1864, the Diné endured the Long Walk, a forced relocation from Arizona to New Mexico. The Trail of Tears in 1868 removed the Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw Nations to Oklahoma. All nomadic tribes north of Mexico were relocated to reservations.

The forced removal of American Indians to reservations and the destruction of traditional food sources were deliberate governmental efforts to terminate Native peoples. In 1867, a colonel in the U.S. Army said, “Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.”

Destructive efforts continued far into the 20th century. Native children were removed from their families and communities to boarding schools. Children experienced forced assimilation that brought neglect, abuse, oppression, and intergenerational trauma. The impact is still felt as Tribal Nations actively work to reclaim their language, culture, and traditional foodways.

The federal government discouraged American Indians and Alaska Natives from continuing their traditional hunting and gathering traditions and provided food rations known as commodity foods – lard, flour, coffee, sugar, and canned meat (also known as spam) – to Native communities. Such food products are completely foreign to the traditional Native diet. The distribution of commodities created dramatic dietary changes among Native people.

The government never provided enough food to feed all tribal members, and the diet is linked to a multitude of poor health outcomes, including diabetes. Combined with the destruction of traditional practices, the diet of the present day has contributed to the disparities in health faced by Native people.

Food Deserts

Food Deserts

Today, Native people disproportionately experience lower life expectancy, more chronic health conditions, disease, violence, poverty, and an overall lower quality of life – as well as food insecurity. For elders who no longer drive or those without access to a car or transportation, healthy food choices can be hard to access. Low access to healthy food options combined with poverty and other factors means that many Native people face what is known as “food insecurity” — the inability to access a sufficient quantity of affordable nutritious food due to a lack of money or resources. Almost one of every four Native households face food insecurity. There is also evidence to show that even those who have access to healthy choices often find them to be unaffordable.

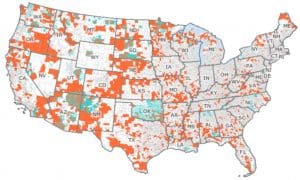

Elders living on a reservation or in a rural area may have very limited options about where to purchase food as well as difficulty accessing those places at all. Many live in what is known as a “food desert” — defined as parts of the country (usually low-income areas) with few or no affordable healthy food choices like access to fresh fruit, vegetables and other healthful whole foods. A food desert can exist both in rural areas and large cities alike. This means that the places many elders call home may only have access to fast food or convenience stores, rather than healthy foods. People often resort to eating commodity foods and overly processed foods sold at convenience stores or fast food restaurants.

Those eating a contemporary western diet now experience processed foods high in simple carbohydrates (refined sugar), salts and fats. One example of such a food that is commonly found in Indian County is frybread. Frybread found today is a product of the shift from traditional foods to government-issued commodities. Frybread and foods like it — whether homemade or store-bought — have little nutritional value and can negatively impact health.

4. Tribal Food Sovereignty

The Seven Pillars of Food Sovereignty

- Focus on food for people

- Build knowledge and skills

- Work with nature

- Value food providers

- Localize food systems

- Put control locally

- Food is sacred

Tribal Nations are restoring traditional food systems and rebuilding relationships with the land, water, plants, and animals. Food sovereignty is an act of self-determination that revitalizes the local economy, cultural identity and traditions, health and wellness, language, community, and family.

How to Create or Expand a Traditional Food System

How to Create or Expand a Traditional Food System

Native communities can begin by conducting a food sovereignty assessment to understand their current food system and plan how to regain control of their local food system. The First Nations Development Institute has a Food Sovereignty Assessment Tool that could be adapted to the local community and includes information on who participates, how to collect data, survey questions, a process for asset mapping, developing, and implementing local plans. Topics assessed are:

- Community food resources

- Food assistance

- Diet and health

- Culture

- Food and agriculture-related business enterprises

- Natural resources and environment

Sicangu Food Sovereignty Initiative

The Sicangu Food Sovereignty Initiative (SFSI) was developed by the Rosebud of South Dakota with input from community elders, local producers, and partner organizations. The SFSI represents one of 12 areas in a seven-generation plan, spanning 175 years.

The SFSI has seven goals:

- Regenerative agriculture will be used for all food production within the boundaries of Rosebud. For example, farms will use no-till practices, and plant cover crops to replenish soil nutrients.

- All institutions serving Rosebud will utilize local and traditional ingredients.

- Infrastructure will be in place to facilitate equitable access to nutritious food for all communities. For example, the state and federal food codes do not account for traditional harvesting and food preparation techniques, so a Tribal food code will be created. A second effort is to organize small local farmers to collectively sell their produce to meet the supply demands of Rosebud’s institutional food market (schools, stores, etc.). Third, SFSI provides a mobile grocery market, which sources from local producers. The mobile grocery market is steadily increasing demand and eventually all remote communities can be supported year round.

- Food will again be seen as medicine that heals the body, mind, and spirit of the Oyate, and deepens Lakota identity. The community is returning the ceremonial aspect of food while harvesting, preparing, and sharing food.

- The food system will foster and support sustainable business ventures, making food production and entrepreneurship a viable pathway for job creation and income generation. Because access to capital is a challenge, a community development institution on the Rosebud Reservation was established and provides non-predatory loans to business owners, including food entrepreneurs.

- Youth will be empowered to lead their families back to self-determination by knowing how to grow, harvest, and prepare foods of their choice. The local school system will include a food sovereignty curriculum, and a dual enrollment program with Sinte Gleska University on how to grow, harvest and prepare foods using both traditional and modern techniques.

- Tribal citizens will be empowered to make highly informed consumption decisions. An economy and education centered around food as medicine will achieve self-determination and strengthen the Lakota identity.

Decolonizing Diet

Some activists in partnership with Tribal Nations and universities have begun to push for a return to traditional Native diets. One such movement is the “Decolonizing Diet Project” started by Professor Marty Reinhardt at Northern Michigan University. The Decolonizing Diet Project takes the perspective that the change in dietary practices that resulted from the colonization of North America is a form of oppression. This project and others like it in Native communities across America are researching what foods existed in the traditional diet prior to colonization.

Broadly, these types of projects share common objectives. By engaging elders, the knowledge of generations is built and shared among the community in support of the local food system. Such programs also educate communities about traditional diets and the importance of embracing and reviving traditional practices. These programs also help increase physical activity among Native people by encouraging hunting, gathering, gardening and traditional preparation of food. They also promote the preservation of culture as well as access to healthy, traditional foods within Native communities.

Examples of Food Sovereignty Activities

Examples of Food Sovereignty Activities

- Food cultivation through Tribal farms, community, school, and family gardens.

- Health Fairs with information about gathering/harvesting, growing, eating, and cooking traditionally.

- Expanded availability of healthy foods via mobile grocery markets, and at local farmer’s markets, worksites, schools, restaurants, convenience stores, grocery stores, and celebrations.

- Sharing traditional cultivation, gathering, hunting, fishing, harvesting, and sharing of food through storytelling, digital stories (elders and youth collaborate) and organized physical activities such as gathering native foods, games, fun runs, land restoration work, canoeing, dances, etc.

- Professional development for food entrepreneurs in the form of workshops, seminars, and ongoing business planning and support.

- Elders teach youth in school, at summer camps, and in summer jobs programs about gathering, growing, hunting, fishing, cooking, preserving, storing, and cultural traditions connected to food such as prayers, songs, and dances.

- Heirloom seed saving and seed banks

- Composting workshops

- Children become teachers and share health messages with their families.

Diet Recommendations

Many, if not all, Native cultures teach, “Food is medicine.” Eating a healthy diet can be a challenge due to food deserts, the unhealthy nature of commodities, the convenience of fast foods, and limited resources to buy fresh foods. However, you can begin slowly and prepare healthy traditional recipes and cook with traditional ingredients that can preserve and promote your culture. Consider the benefits of living by the belief, “Food is medicine.”

All elders can benefit from a healthier diet. Make one change at a time. Changing diets is not easy and habits can be hard to break. By making one change at a time, it will be easier to change habits successfully. Here’s how to get started:

- Eat whole foods like corn, beans, lentils, chickpeas, and grains like wild rice, quinoa, and buckwheat.

- Eat fresh fruits and vegetables, especially dark green, red, and orange vegetables such as bell peppers, berries, apples, squash, and salads.

- Eat small portions of healthy proteins like nuts, seeds, eggs, pasture-fed meat, and wild fish.

- Snack on whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds.

- Cook by sautéing, baking, broiling, roasting, boiling, and steaming. (Avoid fried foods.)

- Add flavor with spices and herbs.

- Use healthy traditional oils, e.g., seal oil (if available) or avocado, olive, and expeller-expressed sesame oils. Avoid processed seed and vegetable oils like soybean, cottonseed, sunflower, and canola.

- Drink several glasses of water each day. Drink tea and coffee without sugar.

- Avoid sugary drinks such as soda, juices, and beverages with high fructose corn syrup. Avoid high-sugar foods like chips, sweet breads, cakes, and candy.

- Avoid processed foods, which are generally found in the middle (the aisles) of grocery stores. Dairy, fruits, vegetables, meat, and fish are located around the perimeter of grocery stores and are healthier food choices.

- Learn about and participate in your Tribal community’s traditional foodways.

- Try traditional recipes and traditional ingredients. Eating traditional foods can be a healthy choice that preserves and promotes culture.